nalco group

bone, muscle & joint pain physio

BOOK NOW / WHATSAPP ABOUT YOUR PAIN OR INJURY

- ORCHARD 400 Orchard Road #12-12 Singapore 238875

- TAMPINES 9 Tampines Grande #01-20 Singapore 528735

- SERANGOON 265 Serangoon Central Drive #04-269 Singapore 550265

Home > Blog > Hand Therapy > Trigger Finger

Trigger Finger

Trigger finger is a disorder characterized by catching or locking of the involved finger.[2] Pain may occur in the palm of the hand or knuckles.[3] The name is due to the popping sound made by the affected finger when moved.[2] Most commonly the index finger or thumb is affected.[1]

Risk factors include repeated injury, diabetes, kidney disease, thyroid disease, and inflammatory disease.[3] The underlying mechanism involves the tendon sheath being too narrow for the flexor tendon.[3] This typically occurs at the level of the A1 pulley.[2] While often referred to as a type of stenosing tenosynovitis, little inflammation appears to be present.[3] Diagnosis is typically based on symptoms after excluding other possible causes.[2]

Initial treatment is generally with rest, splinting the finger, NSAIDs, or steroid injections.[3] If this is not effective surgery may be used.[3] Trigger finger is relatively common.[2] Females are affected more often than males.[3] Those in their 50s and 60s are most commonly affected.[2] The condition was formally described in 1850.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms include catching or locking of the involved finger.[2] As the disease progresses pain may occur in the palm of the hand of knuckles.[3]

causes

The cause of trigger finger is unclear but several causes have been proposed.[2] It has also been called stenosing tenosynovitis (specifically digital tenosynovitis stenosans), but this may be a misnomer, as inflammation is not a predominant feature.

It has been speculated that repetitive forceful use of a digit leads to narrowing of the fibrous digital sheath in which it runs, but there is little scientific data to support this theory. The relationship of trigger finger to work activities is debatable and scientific evidence for[4] and against[5] hand use as a cause exist. While the mechanism is unclear, there is some evidence that triggering of the thumb is more likely to occur following surgery for carpal tunnel syndrome.[6] It may also occur in rheumatoid arthritis.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is made almost exclusively by history and physical examination alone. More than one finger may be affected at a time, though it usually affects the index, thumb, middle, or ring finger. The triggering is usually more pronounced late at night and into the morning, or while gripping an object firmly.

Treatment

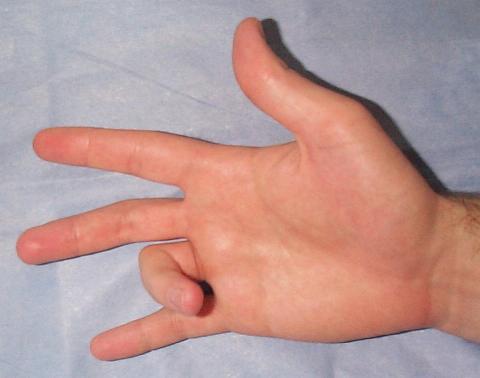

Post operative photo of trigger finger release surgery in a diabetic patient. See:[7]

Injection of the tendon sheath with a corticosteroid is effective over weeks to months in more than half of people.[8]

When corticosteroid injection fails, the problem is predictably resolved by a relatively simple surgical procedure (usually outpatient, under local anesthesia). The surgeon will cut the sheath that is restricting the tendon.

One recent study in the Journal of Hand Surgery suggests that the most cost-effective treatment is two trials of corticosteroid injection, followed by open release of the first annular pulley.[9] Choosing surgery immediately is the most expensive option and is often not necessary for resolution of symptoms.[9] More recently, a randomized controlled trial comparing corticosteroid injection with needle release and open release of the A1 pulley reported that only 57% of patients responded to corticosteroid injection (defined as being free of triggering symptoms for greater than six months). This is compared to a percutaneous needle release (100% success rate) and open release (100% success rate).[10] This is somewhat consistent with the most recent Cochrane Systematic Review of corticosteroid injection for trigger finger which found only two pseudo-randomized controlled trials for a total pooled success rate of only 37%.[11] However, this systematic review has not been updated since 2009.

There is a theoretical greater risk of nerve damage associated with the percutaneous needle release as the technique is performed without seeing the A1 pulley.[12]

Thread trigger finger release is an ultrasound guided minimally invasive procedure using a piece of dissecting thread to transect A1 pulley without incision.

Prognosis

The natural history of disease for trigger finger remains uncertain.

There is some evidence that idiopathic trigger finger behaves differently in people with diabetes.[8]

Recurrent triggering is unusual after successful injection and rare after successful surgery.

While difficulty extending the proximal interphalangeal joint may persist for months, it benefits from exercises to stretch the finger straighter.

references

- "Trigger Finger - Trigger Thumb". OrthoInfo - AAOS. March 2018. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- Makkouk AH, Oetgen ME, Swigart CR, Dodds SD (June 2008). "Trigger finger: etiology, evaluation, and treatment". Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 1 (2): 92–6. doi:10.1007/s12178-007-9012-1. PMC 2684207. PMID 19468879.

- Hubbard, MJ; Hildebrand, BA; Battafarano, MM; Battafarano, DF (June 2018). "Common Soft Tissue Musculoskeletal Pain Disorders". Primary care. 45 (2): 289–303. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2018.02.006. PMID 29759125.

- Gorsche R, Wiley JP, Renger R, Brant R, Gemer TY, Sasyniuk TM (June 1998). "Prevalence and incidence of stenosing flexor tenosynovitis (trigger finger) in a meat-packing plant". J Occup Environ Med. 40 (6): 556–60. doi:10.1097/00043764-199806000-00008. PMID 9636936.

- Kasdan ML, Leis VM, Lewis K, Kasdan AS (November 1996). "Trigger finger: not always work related". J Ky Med Assoc. 94 (11): 498–9. PMID 8973080.

- King, Bradley A.; Stern, Peter J.; Kiefhaber, Thomas R. (2013). "The incidence of trigger finger or de Quervain's tendinitis after carpal tunnel release". Journal of Hand Surgery (European Volume). 38 (1): 82–3. doi:10.1177/1753193412453424. PMID 22791612.

- Eisen, Jonathan. "Trigger finger surgery. Fun". Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- Baumgarten KM, Gerlach D, Boyer MI (December 2007). "Corticosteroid injection in diabetic patients with trigger finger. A prospective, randomized, controlled double-blinded study". Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 89 (12): 2604–2611. doi:10.2106/JBJS.G.00230. PMID 18056491.

- Kerrigan CL, Stanwix MG (Jul–Aug 2009). "Using evidence to minimize the cost of trigger finger care". J Hand Surg Am. 34 (6): 997–1005. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2009.02.029. PMID 19643287.

- Sato SS, et al. (2012). "Treatment of trigger finger: randomized clinical trial comparing the methods of corticosteroid injection, percutaneous release and open surgery". Rheumatology. 51 (1): 93–99. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/ker315. PMID 22039269.

- Peters-Veluthamaningal, C; van der Windt, DA; Winters, JC; Meyboom-de Jong, B (Jan 21, 2009). "Corticosteroid injection for trigger finger in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD005617. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005617.pub2. PMID 19160256.

- Bain, GI; Turnbull, J; Charles, MN; Roth, JH; Richards, RS (Sep 1995). "Percutaneous A1 pulley release: a cadaveric study". The Journal of hand surgery. 20 (5): 781–4, discussion 785–6. doi:10.1016/S0363-5023(05)80430-7. PMID 8522744.