nalco group

bone, muscle & joint pain physio

BOOK NOW / WHATSAPP ABOUT YOUR PAIN OR INJURY

- NOVENA 10 Sinaran Drive, Novena Medical Center #10-09, Singapore 307506

- TAMPINES 9 Tampines Grande #01-20 Singapore 528735

- SERANGOON 265 Serangoon Central Drive #04-269 Singapore 550265

Home > Blog > What Are The Injury Risks For A Beginner Runner?

What Are The Injury Risks For A Beginner Runner?

Little gear is required with running that it truly is one of the easiest and most accessible sport to do here in Singapore where the weather is quite predictable 365 days a year (hot).

Running has great health affects in helping weight loss as well as quitting smoking (Nielson et al, 2012).

Due to the popularity of people choosing running as their preferred training routine, it is important to look at risks that can cause injury.

Looking at new runners and behavior and demographic factors, it’s interesting to note that, a study showed Type A personalities in new runners actually prevents injuries.

Having a BMI > 30kg/m2 increases injury risks and injuries.

And being in the age group of 45-65 had higher incidence of injuries compared to other age groups (Nielson, 2014).

Medial tibial stress syndrome was the most common among beginner runners (Kluitenberg et al., 2014).

Medial tibial stress syndrome, Achilles tendinopathy and plantar fasciitis were main injuries sustained by running; Achilles tendinopathy and patellofemoral syndrome were most common in ultramarathon runners (Lopes et al, 2012).

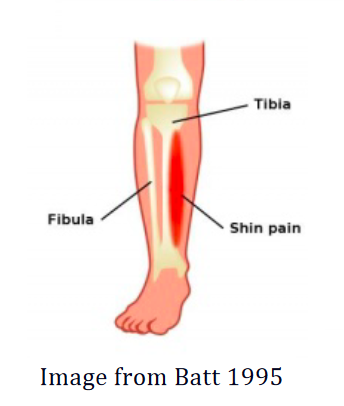

Shin Splints = Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome

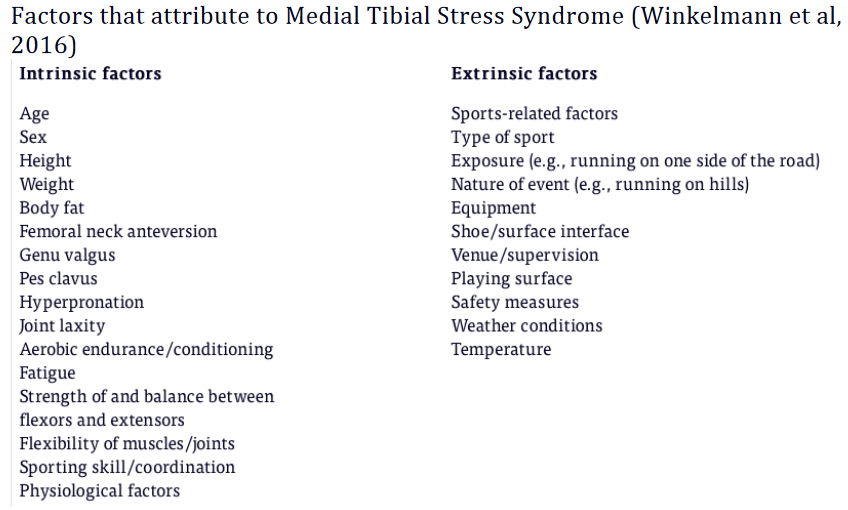

Medial tibial stress syndrome is a common injury found in athletes and soldiers.

The lay man’s term is “shin splints.”

The name is given based on the symptoms felt at the lower leg (inner lower leg/tibial border) during exercise and can be felt when touched at the tibia (lower leg) over at least 5 cm. Overload adaptation to the bone is found as reason for the pain in bone scan, MR or CT scan (Moen 2009).

Cause of injury is due to a runner increasing duration, intenstiy or distance in training (Galbraith 2009).

Achilles Tendinopathy

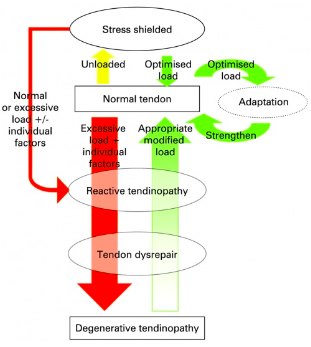

Achilles tendinopathy is an overuse injury due to repeated storage and release of eneryg with excessive compression of the tendon. Lack of flexibility or stiffness can increase injury.

When treating tendon pain a new strategy by classifiying degree of changes in the tendon as: reactive, disrepair and degenerative tendinopathy is used in the tendon continuum to add or decrease load in reducing pain (Clain et al, 1992).

Current physiotherapy treatments for Achilles tendinopathy include joint mobilizations for restricted movement, controlled tendon loading through proper exercise regime, taping, and anti-inflammatory modalities.

Plantar Fasciitis

Many different causes of pain in the plantar heel besides the plantar fascia exist so "

Plantar Heel Pain

" serves best to include a broader description when discussing this and related pathology (Lemon 2003). When weight is put through the foot, the lower leg loads and creates tension through the plantar fascia; it is this tension, called the windlass mechanism, that adds critical stability to the loaded foot with minimal muscle activity (Tweed 2009).

Some risk factors that contribute to plantar heel pain include: decreased range of motion (dorsiflexion) in ankle, flat foot when moving, high impact loaded and prolonged standing, poor shoe fit, diabetes and high BMI.

Symptoms include pain at bottom of heel, usually worse in morning first few steps or after inactivity, greater pain after exercises (not during)

Physiotherapy treatments include strength and stretching routine, night splints, joint mobilizations, ultrasound, taping, orthotics, and modalities such as shockwave (Thomas et al, 2010).

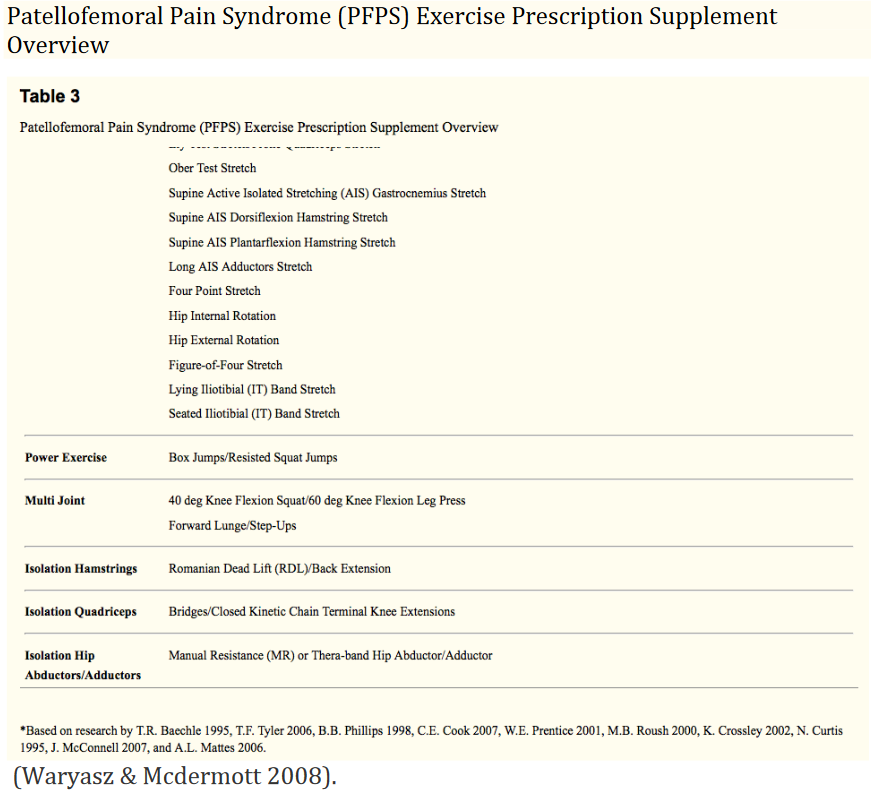

Patellofemoral Pain (PFPS)

Patellofemoral pain is a general term to include pain in the knee, the surrouding soft tissue and in front or behind the knee.

Muscular etiologies of PFPS

Etiology & Pathophysiology

Weakness in the quadriceps

- It may adversely affect the PF mechanism.

- Strengthening is often recommended.

Weakness in the medial quadriceps

- It allows the patella to track too far laterally.

- Strengthening of the VMO is often recommended.

Tight iliotibial band

- It places excessive lateral force on the patella and can also externally rotate the tibia, upsetting the balance of the PF mechanism. This can lead to excessive lateral tracking of the patella.

Tight hamstrings muscles

- It places more posterior force on the knee, causing pressure between the patella and the femur to increase.

Weakness of tightness in the hip muscles

- Dysfunction of the hip external rotators results in compensatory foot pronation.

Tight calf muscles

- It can lead to compensatory foot pronation and can increase the posterior force on the knee.

Injury risks in Running

Knobloch et al (2008) reported more incidence of shin splints among individuals running more than five days per week.

That said, another study by Fields et al, (1990) questioned the factor of distance as an injury risk, since they found injured runners averaging essentially the same mileage as healthy runners.

The distance increase was accompanied by the experience gained as a runner, which possibly can explain the reduced risk of injury as weekly mileage increase; matured runners may be able to understand their body injury thresholds better than novice runners.

To explain this clearly, the study compared a 1000 hours of running between novice runners and marathon runners. New runners running 30 minutes three times a week over 26 weeks equates to 39 hours (with risk injury 33 per 1000 hours as cited by Buist et al, 2008).

This would produce injury risk with novice runners at 1.29 injuries compared to marathon runners 1.15 injures with 156 hours (2 hours, 3 times a week) over 26 weeks. In this theoretical model, the absolute number of injuries is higher in novice runners. However, overall, the increment of risk of injury increases as weekly mileage increases (Walter et al, 1989)

Volume and Frequency

Through meta-analysis of articles, authors have recommended an increase in weekly volume to no more than 10% per week (the 10% rule) to reduce injury risk (Paty 1984 & Johnson et al, 2003). The frequency in running demonstrates a “U-shape” pattern in that those who trained one time a week and thosw who trained 6-7 times a week had higher risk of running injuries (Nielson et al, 2012).

These factors of volume, duration, intensity, and frequency seem to have a complex interaction and cannot be looked at singularly when looking at injury risks.

Of all the modifiable risk factors studied, weekly distance is the best predictor of possible injuries.

For recreational runners with injuries, especially within the past year, a decrease in distance to below 32 km per week is recommended. For those starting a running programme, moderation is the best advice. For competitive runners, focus should be taken to ensure that prior injuries are properly healed before attempting any race, espeically a marathon (Macera 1992).

For recreational runners, going over 65 km per week increased injury risks as found in two high quality studies (Macera 1989 & Walter et al 1989).

References

Batt, Mark E. "Shin Splints - A Review of Terminology." Clinical journal of sport medicine 5.1 (1995): 53-57.

Buist I, Bredeweg SW, van Mechelen W, Lemmink KA, Pepping GJ, Diercks RL. No effect of a graded training program on the number of running-related injuries in novice runners: A randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(1):33–39

Clain, Michael R., and Donald E. Baxter. "Achilles tendinitis." Foot and Ankle International 13.8 (1992): 482-487.

Fields KB, Delaney M, Hinkle JS. A prospective study of type A behavior and running injuries. J Fam Pract. 1990;30(4):425–429

Galbraith RM, Lavalee ME (2009). 'Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Conservative Treatment Options', Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2(3), pp. 127-133.

Johnston CA, Taunton JE, Lloyd-Smith DR, McKenzie DC. Preventing running injuries. practical approach for family doctors. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:1101–1109

Knobloch K, Yoon U, Vogt PM. Acute and overuse injuries correlated to hours of training in master running athletes. Foot Ankle Int. 2008;29 (7):671–676

Kluitenberg B, van Middelkoop M, Smits DW, et al. The NLstart2run study: incidence and risk factors of running-related injuries in novice runners. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2014;. doi: 10.1111/sms.12346 (Epub 2014 Dec 1).

Lemont H, Ammirati KM, Usen N. Plantar fasciitis: a degenerative process (fasciosis) without inflammation. J A m Podiatr Med Assoc. 2003;93(3):234–7

Macera CA. Lower extremity injuries in runners. advances in prediction. Sports Med. 1992;13(1):50–57

Macera C A, Pate R R, Powell K E, et al. Predicting lower-extremity injuries among habitual runners. Arch Intern Med 1989;149:2565–8

Moen, M. H., Tol, J. L., Weir, A., Steunebrink, M., & Winter, T. C. (2009). Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome. Sports Medicine,39 (7), 523-546. doi:10.2165/00007256-200939070-00002

Paty JG, Jr., Swafford D. Adolescent running injuries. J Adolesc Health Care. 1984; 5 (2): 87–90

Nielsen RO, Buist I, Sorensen H, et al. Training errors and running relatedinjuries: a systematic review. Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2012;7:58–75.

Nielsen RO, Rønnow L, Rasmussen S, et al. A prospective study on time to recovery in 254 injured novice runners. PloS one. 2014;9:e99877.

Tweed JL, Barnes MR, Allen MJ, Campbell J a. Biomechanical consequences of total plantar fasciotomy: a review of the literature. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2009;99(5):422–30.

Thomas JL, Christensen JC, Kravitz SR, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of heel pain: a clinical practice guideline-revision 2010. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2010;49(3 Suppl):S1–19.

Walter SD, Hart LE, McIntosh JM, Sutton JR. The ontario cohort study of running-related injuries. Arch Intern Med. 1989; 149 (11):2561–2564

Waryasz, G. R., & Mcdermott, A. Y. (2008). Patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS): A systematic review of anatomy and potential risk factors. Dynamic Medicine,7 (1), 9. doi:10.1186/1476-5918-7-9

Winkelmann, Z. K., Anderson, D., Games, K. E., & Eberman, L. E. (2016). Risk Factors for Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome in Active Individuals: An Evidence-Based Review. Journal of athletic training, 51(12), 1049-1052